The second half of the 19th Century saw the introduction into Britain of the completely self-contained cartridge starting with the pinfire system and going into a centrefire cartridge later in the Century. These enabled much easier and rapid loading for the Victorian sportsman but could produce problems in the field through cartridge cases becoming stuck in the breech of the barrel.

Until the 1960’s shotgun cartridge cases were made from paper with a brass head and could be affected by damp atmospheric conditions, rain and heat. These conditions together with the effect of discharging the cartridge could all make the case swell up slightly resulting in an expanded empty case stuck in the breech. The same problem was found by hunters using rifles in the tropics where brass cases could expand in the heat and corrode badly in the high humidity. Early rifle cases were coiled brass, sometimes paper covered, with iron bases and not as robust as the later drawn brass cases. Fingers often weren’t strong enough to withdraw the cartridge and stuck cases could also jam the complete opening of the gun. Another problem encountered was pulling the base of the cartridge off the paper or coiled brass tube so leaving the remains of the case in the breech which also prevented reloading the gun.

The answer was to produce a tool that helped the sportsman remove the stuck case and any torn parts of the tube. This tested the ingenuity of the Victorian gun implement manufacturers and fuelled a wide variety of designs in a range of qualities which happily has also resulted now in another fascinating area for collectors.

The first completely self-contained cartridges to come into use in Britain during the late 1850’s were pinfire ignition. These relied upon an external pin and internal percussion cap which was detonated when the pin was struck by the hammer of the gun. The cases didn’t have much of a rim on the brass head and the shotguns didn’t have an extractor so removal of the cartridge was made by pulling the cartridge backwards by the pin.

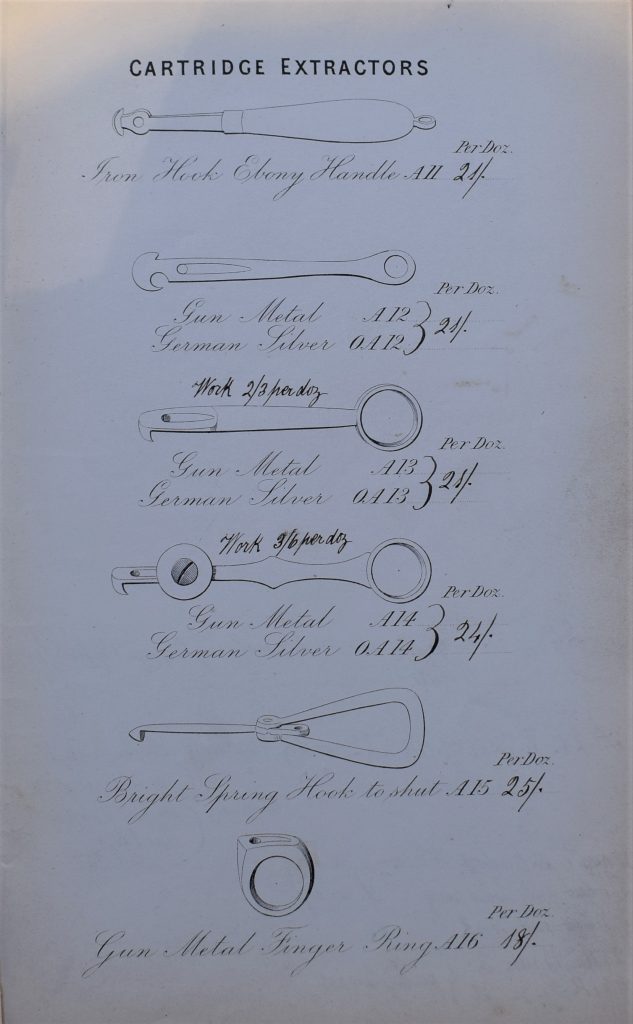

The first cartridge extracting tools were generally made from iron and utilised a hook which could be used to pull the pin or retrieve the remnants of any torn paper case from the breech.

More expensive versions of the simple iron hook were designed to be easier to carry in a pocket by using a similar design to a folding button hook inside a hoop and this design of extractor was registered on 27th August 1859 by Henry Elliott, gunmaker of Birmingham under design no. 4198 described as a “cartridge case drawer”.

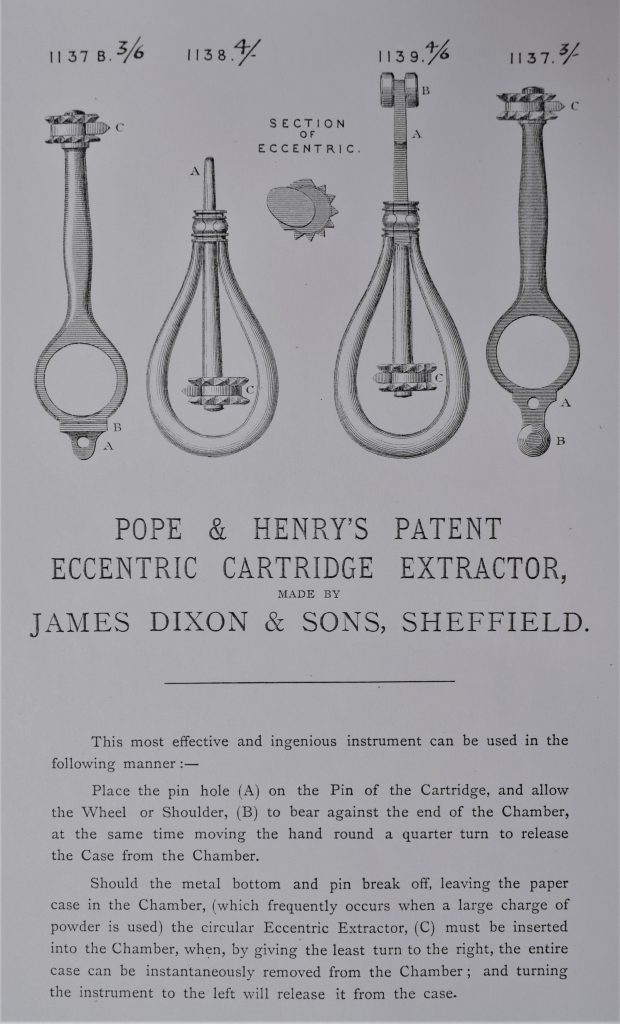

This idea of a loop with a swivelling extractor arm was subsequently taken a stage further by the Sheffield gun implement manufacturers James Dixon & Sons and William Bartram who each produced an improved version. Bartram used a large wheel behind the pin slot to act as a fulcrum. Dixon’s version had a double roller in front of the pin slot and was also fitted with Pope & Henry’s Patent which was an eccentric wheel in gunmetal at the other end of the extractor arm to snag any torn paper case still stuck in the breech and enable it to be removed.

Another pattern of very early pinfire extractors embodied a pair of pliers which could be used to grip the slight rim on the base of the cartridge in addition to a hole through which the pin could be slotted and a hook on one arm to retrieve a torn case. This pattern is extremely rare but two examples can be seen in the following photos. The quality of the steel tool is exceptional and whilst un named has the appearance of being made by a surgical instrument manufacturer. An identical tool is shown in Richard Akehursts book “Game Guns and Rifles” on plate 35 included in the tools cased with a pinfire shotgun made by John Dickson gunmakers of Edinburgh in 1865.

As the 19th Century progressed the majority of pinfire extractors were manufactured by the three large Sheffield gun implement makers: James Dixon & Sons, G & J.W. Hawksley and William Bartram, all of whom had a long history of working in non-ferrous metals and so, in addition to iron and steel, manufacturing materials began to include brass, gun metal (a bronze type alloy) and nickel silver.

Three early pinfire extractors by G & J.W. Hawksley. The outer two are made in gunmetal and the middle tool is in nickel silver.

Three early pinfire extractors by G & J.W. Hawksley. The outer two are made in gunmetal and the middle tool is in nickel silver.

Although the three Hawksley extractors shown above are of a similar pattern the bottom extractor features an improvement – a wheel has been fitted by the pin slot which can be used as a fulcrum against the breech of the gun to lever out the stuck case.

The Dixon catalogue page refers to Pope & Henry’s Patent but this is usually just stamped as “Popes Patent” on the gunmetal eccentric wheel at the end of the extractor.

As time progressed the pattern or style of pinfire extractors began to standardise. The fulcrum wheel became common and many featured a loop in the centre to thread your finger into to assist in pulling or levering the case out.

The last pinfire extractor I would like to show you is an intriguing dual purpose pin or centre fire extractor combined with a rammer and closer by G & J.W. Hawksley. This is the only one I have seen and it doesn’t appear in any of the Hawksley catalogues I have. Is this experimental? It is an odd combination. It is quite heavy and at 5″ long too big to be practical to carry in the pocket with all the other shooting paraphernalia so would only have been used in possibly the gunroom, in which case why would you need an extractor?

The advent of the centrefire cartridge heralded, if anything, an even wider range of designs for cartridge extractors. In the main they relied on a 2 or 3 prong claw to fit over the rim of the cartridge base allowing a straight pull. It wasn’t possible to provide any leverage. The cheapest and most basic tool was the finger ring extractor which was extensively sold at every gunsmiths and ironmongers shop.

Probably next was a long handled 2 prong extractor. As the slots inside the prongs were slightly angled this extractor does fit on the base rim surprisingly securely. These extractors are now much scarcer than three prong so this may mean that they weren’t so popular at the time. The lower two Dixon extractors in the photograph below have a hook at the opposite end to the claw to use in removing torn cases from the breech.

Unlike pinfire, centrefire cartridge extractors had to be made for specific bore sizes as they relied on fitting accurately and securely on the rim of the cartridge base. In shotgun calibres, I have seen extractors ranging in size from .410″ up to 4 Bore so here are a few examples of different patterns of extractors in a selection of the larger sizes.

As always manufacturers offered a range of qualities both in complexity and materials going from the basic two prong claw brass ring extractor up to the long three prong claw in solid nickel silver with Popes patent . They also decided to expand their product range by combining the extractor with a variety of other tools which provided extra features for the sportsman such as whistles, striker keys, turnscrews, carriage keys and even game despatchers. In the following photos you can see some of the variations and interesting combinations produced.

Many sportsmen owned and used a range of guns of different calibres and so an adjustable extractor would have proved very useful. James Dixon & Sons recognised this and produced a small hoop extractor with a centre wheel which, when rotated, opened or closed the two pronged claw at the end of the hoop to fit a limited range of different bore sizes.

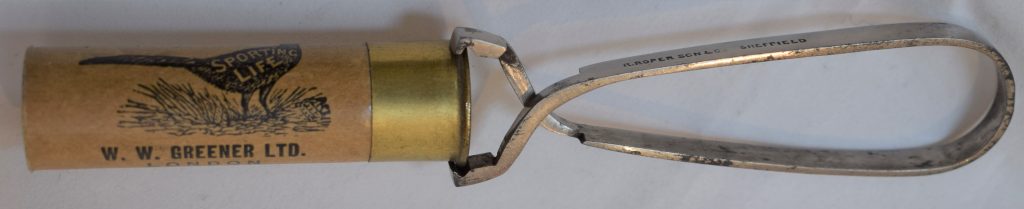

A later development in the history of the cartridge extractor was an infinitely variable extractor which consisted of a plated spring steel hoop which when squeezed opened the claw to suit a larger variety of bore sizes. Robert Roper, a gunmaker in Sheffield registered a design for a cartridge extractor on 10th February 1881 under registration design no. 3398.

Modern cartridge extractors often have cup shaped claws rather than two or three pronged claws. However this isn’t a recent development as James Dixon started to manufacture this pattern in the late 19th Century.

Extractors were also produced in a much lower quantities for rifle calibres and cased double rifles of the Victorian period usually had a suitable extractor fitted into the case. Rifle extractors are much rarer than the shotgun extractors and I have seen them in the popular Victorian big game double rifle calibres .380, .400, .450, .500 and .577. They aren’t usually combined with other tools apart from occasionally Popes Patent.

Until recently I wasn’t aware of any extractors for pistol cartridges, but amazingly, within a short space of time, I acquired two. Both are made by Bussey & Co. London and as one came in the case of a Tranter .32 rimfire revolver I wonder if they were just made for rimfire revolvers. They are tiny (2 3/8″ long) and use the cup type claw. These two are the only ones I have ever seen.

Lastly to complete the story of the cartridge extractor it is only fair to mention those fitted to folding sportsman’s knives. These knives traditionally were made with a main blade, pen blade, saw, scissors, awl, lancet, tweezers and corkscrew and had been manufactured by a multitude of Sheffield and London cutlers since the early 1800’s. In the last quarter of the 19th Century, following the development of the centrefire breech loader a useful additional tool for the knife was of course a cartridge extractor and many knives were subsequently manufactured with either extractors as part of the guard or with a folding extractor fitted inside the scales which acted on one of the back springs.

I hope you have enjoyed this brief story of the cartridge extractor. I am sure there are many patterns I have yet to come across and if anyone has any other unusual or complicated variations I would love to hear from you.